Tenth Circuit Affirms ALJ’s Use of Preamble in Awarding Black Lung Benefits (Blue Mountain Energy v. Director, OWCP [Gunderson])

On Friday, November 13, 2015, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Tenth Circuit issued a published decision in Blue Mountain Energy v. Director, OWCP [Gunderson II], 805 F.3d 1254 (slip opinion available here).

The court rejected the coal company’s challenge to the ALJ’s use of an important document in federal black lung benefits litigation: the Department of Labor’s “preamble” to the 2000 amendments to the black lung regulations (available at 65 Fed. Reg. 79,920). The preamble is important because it provides the medical principles that underlie the Department of Labor’s current regulations. The preamble’s 126-pages discuss the medical literature in detail and serve as a nonbinding resource relevant to considerations of how medical questions should be resolved under the black lung regulations.

With Gunderson II, the 10th Circuit joins every other U.S. Court of Appeals to consider this issue—the 3rd, 4th, 6th, 7th, and 9th—in holding that ALJs can properly use to the preamble in individual miner’s cases. (See previous posts describing decisions by the 9th Circuit, 6th Circuit, 4th Circuit, and 3rd Circuit.)

Facts

Terry Gunderson filed a claim for black lung benefits in 2001 and, over the subsequent fourteen years, litigated with his former employer, Blue Mountain Energy, about whether his COPD was related to his 30 years of coal-mine dust exposure or whether it was due solely to his 34 years of cigarette smoking.

The ALJs job was to weigh the varying opinions from Drs. Repsher and Renn for the employer and Drs. Shockey, Parker, and Cohen for Mr. Gunderson.

After the ALJ denied Mr. Gunderson benefits, he appealed all the way up to the 10th Circuit, which held in his favor in Gunderson v. U.S. Dep’t of Labor, 601 F.3d 1013 (10th Cir. 2010). In the 2010 decision (referred to as Gunderson I), the court held that the ALJ did not sufficiently explain the basis of his denial, especially considering the “substantial inquiry by the Department of Labor” into the science around pneumoconiosis.

Following remand by the court, the ALJ again denied benefits, but the Benefits Review Board vacated this decision and remanded it back to the ALJ with instructions that the ALJ did not have to determine the experts’ credibility in light of the preamble.

On the second remand, the ALJ awarded benefits, finding reasons to credit Drs. Parker and Cohen over Drs. Renn and Repsher. The ALJ provided multiple reasons for his credibility decisions, but at two points referred to the preamble. On the one hand, the ALJ criticized Dr. Repsher’s failure to address the potentially additive effects of coal-mine dust and cigarette smoke by pointing to the preamble’s acknowledgment of the additive effects. On the other hand, the ALJ credited Dr. Parker in part because Dr. Parker cited to literature about the effect of coal-mine dust on miner’s symptoms that was cited approvingly in the preamble.

After the ALJ denied Blue Mountain Energy’s request to reopen the record to challenge the preamble’s science, and the Board affirmed the award, Blue Mountain Energy appealed to the 10th Circuit.

10th Circuit Opinion

Blue Mountain presented two issues to the 10th Circuit. The court (in an opinion written by Judge Briscoe and joined by Judges Holmes and Moritz) described them as follows:

Blue Mountain argues that the ALJ violated the [Administrative Procedure Act] by (1) relying on the preamble, thereby giving the preamble the “force and effect of law;” and (2) refusing to reopen the record to allow Blue Mountain to submit evidence challenging the science of the preamble.

The court first noted “the very limited extent to which the ALJ referenced the pream[]ble” and the fact that—as described above—many other circuits have held that ALJs can lawfully use the preamble.

The court rejected Blue Mountain Energy’s argument that “the preamble undeniably changed the outcome” in Mr. Gunderson’s case. The court explained that the procedural background of Mr. Gunderson’s claim alone did not support this contention and that what was notable about the ALJ’s third decision was the rigor with which the reports were analyzed.

As the court explained

We do not read the ALJ’s ruling as invoking the preamble as his only guide. There is no indication in the ALJ’s final opinion that he was effecting some sort of change in the law or relying on a broadly-applicable rule premised on the preamble. Rather, the ALJ appears merely to have used the preamble’s summary of medical and scientific literature as one of his tools in determining whether the experts’ medical analyses of Gunderson’s condition were credible.

. . .

We fail to see how this use of the preamble transforms a summary of “the prevailing view of the medical community” into binding law. Blue Mountain always had the ability to counter the medical opinion of Dr. Parker, as well as the medical literature cited in the preamble. The potential impact of any general principles that may be gleaned from the preamble can always be lessened by evidence that is more case specific or more medically relevant.

After distinguishing the Supreme Court’s decision in Christensen v. Harris County, 529 U.S. 576 (2000), the court concluded its analysis of the preamble:

In sum, we view the preamble as a scientific primer that helps explain why the agency amended the regulation to add “legal pneumoconiosis” to the definition of “pneumoconiosis.” As such, it seems like a reasonable and useful tool for ALJs to use in evaluating the credibility of the science underlying expert reports that address the cause of pneumoconiosis. Accordingly, we join our sister circuits in holding that an ALJ may—but need not—rely on the preamble to 20 C.F.R. § 718.201 for this purpose. This holding does not, as Blue Mountain contends, remove claimants’ burden of proving causation. It merely permits ALJs to use the science described in the preamble to weigh the evidence that the parties offer to prove (or disprove) causation. Of course, parties remain free to offer other scientific materials for the ALJ to consider for the same purpose, including but not limited to, materials challenging the continued validity of the science described in the preamble.

The court then moved on to Blue Energy’s second issue and held that the ALJ did not err by refusing Blue Mountain Energy’s request to reopen the record so that it could offer evidence to rebut the parts of the preamble that the ALJ referred to.

The court explained:

As aptly stated by the Fourth Circuit in Harman, “the APA does not provide that public law documents, like the Act, the regulations, and the preamble, need be made part of the administrative record.” 678 F.3d at 316. Blue Mountain was well aware of the preamble’s scientific findings, e.g., Nat’l Mining. Ass’n v. Dep’t of Labor, 292 F.3d 849 (D.C. Cir. 2002) (industry challenge to the validity of the relevant regulatory amendments, including the preamble), and had ample opportunity prior to the close of this record to submit evidence or expert opinions to persuade the ALJ that the preamble’s findings were no longer valid or were not relevant to the facts of this case. Moreover, its requests to reopen the record—particularly in its motion for reconsideration, when it had the benefit of knowing what in the preamble the ALJ had considered—for the most part did not point to anything in the preamble that it considered no longer scientifically valid.

Analysis

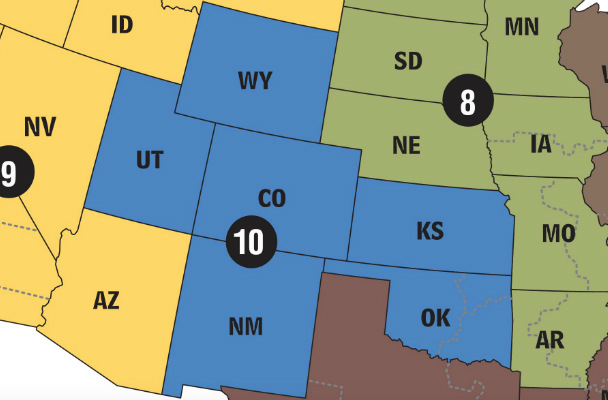

Gunderson II represents another solid piece of precedent in favor of ALJs’ discretion to use the preamble as a nonbinding resource in black lung cases. Because ALJs regularly do so, this does not represent a change in law or practice, but Gunderson II provides further support and should reduce (or at least simplify) future litigation of this issue in the five states forming the Tenth Circuit (Wyoming, Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, Kansas, and Oklahoma).

Gunderson II also stands out for using particularly approving language towards the preamble. The judges’ acknowledgment that the preamble is “scientific primer” and a “reasonable and useful tool for ALJs to use in evaluating the credibility of the science underlying expert reports that address the cause of pneumoconiosis” is useful language that should encourage future judges, law clerks, and others practitioners who work on black lung cases to look to the preamble as a starting point in understanding the scientific issues related to the causes of pneumoconiosis.

Beyond the court’s opinion itself, looking back on Terry Gunderson’s pursuit of benefits, it is striking how long it took him to receive benefits. As explained by Gunderson I, Mr. Gunderson was informed by NIOSH in January of 2001 that he had pneumoconiosis. While this November 2015 decision will likely be the end of the litigation in this case, Mr. Gunderson’s case shows the unfortunately lengthy timelines involved in black lung cases. Luckily for Mr. Gunderson, he was assisted by skilled counsel who were able to represent him in the multiple appeals that his case has involved.

—

Mr. Gunderson was represented by Anne Megan Davis and Thomas E. Johnson of Johnson, Jones, Snelling, Gilbert & Davis PC.

Blue Mountain Energy was represented by Mark E. Solomons and Laura Metcoff Klaus of Greenberg Traurig LLP.

The Director, OWCP was represented by Barry H. Joyner and Gary K. Stearman of the Department of Labor’s Solicitor’s Office.